Introduction

I want to share some fundamental principles I follow to prevent disasters in large software systems. Although these rules are primarily focused on software architecture, they can also be applied to companies and social systems. I’m not an expert in business management or social sciences, so I’ll concentrate on software-related examples. However, you might find these ideas useful in other areas as well.

Complex vs. difficult systems

Why do simple and clear systems become complex over time?

The reason is straightforward, and it comes down to two main factors:

- Unpredictable markets: Markets are constantly evolving and are difficult to predict. Businesses are always searching for new opportunities, and competitors are continuously reshaping the market landscape as we do as well.

- Constant Change: The world is in a state of perpetual change, and the market is no exception. Nothing remains stable for long.

The less a business knows about future needs and market changes, the more uncertain and ambiguous the requirements will be for the tech team. This uncertainty often leads to increasing complexity over time.

Difficult systems

First, let’s clarify what we mean by a “system.” A system is a collection of elements, some of which may function independently, while others are interconnected. Every system is defined by its elements, their behaviors, and the relationships between them. This distinction is crucial because the overall complexity of a system can be minimized if the behaviors and interactions are linear.

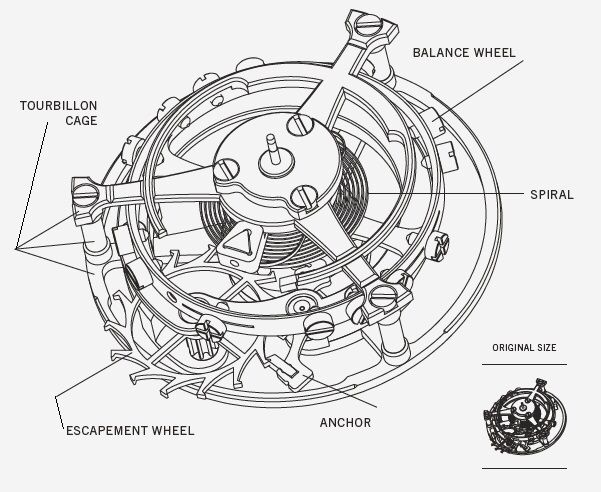

A system can be difficult due to the sheer number of elements involved. For example, consider a mechanical wristwatch with over fifty different components. Despite the high number of parts, each element’s behavior is relatively simple, and the interactions are linear. If one gear slows down by one rotation per minute, the connected gears will also slow down proportionally. This predictability makes the system easier to understand and deconstruct mentally, even if it is intricate.

Complex systems

In contrast to difficult systems, complex systems involve elements with non-linear relationships. This means that a change in one element’s behavior leads to disproportionate changes in others, making the system’s behavior less predictable and harder to calculate. In some cases, these relationships may even be probabilistic, with no clear mathematical function to describe them.

A common example of this in software systems is the number of clients and the volume of requests they generate. This situation represents a specific case of a more general concept: third-party relationships. These involve interactions with external elements—such as third-party services, incoming client traffic, or component suppliers—that lie outside your system’s control.

Collapse of complex systems

As a complex system evolves, the number of non-linear relationships between its elements increases, and the system’s predictability decrease. Eventually, the system can become so complex that even a seemingly trivial, yet unpredictable event can cause it to collapse. After such an event, returning the system to a stable state may become impossible. Mathematical theories like Bifurcation Theory and Catastrophe Theory explain how a small change in a parameter can lead to dramatic shifts in a system’s behavior. A more commonly recognized term for this phenomenon is the Black Swan, frequently referenced in social media.

This is similar to a snow avalanche, where slight changes in temperature, wind, or humidity can trigger the movement of tons of snow. Once the avalanche occurs, it’s irreversible.

This was an introduction to the types of systems we work with. Next time, I’ll dive into the different types of complexity, including size, the illusion of regularity, lack of understanding, and control. I’ll also discuss strategies for managing complexity within your system.